South Sudan Serving as RSF Logistics Hub

South Sudan is increasingly being drawn into Sudan’s brutal civil war, with mounting evidence that its territory has become a covert logistics hub for the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the paramilitary group led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti.

Table Of Content

Despite President Salva Kiir’s government insisting on neutrality, aviation records and diplomatic sources suggest that the South Sudan Civil Aviation Authority (SSCAA) has authorized cargo airlines linked to arms transfers for the RSF. Moldovan-based Pecotox and Kyrgyzstan’s New Way Cargo Airlines are among carriers accused of ferrying weapons, vehicles, and mercenaries through South Sudanese airspace, with flights reportedly routed via Abu Dhabi, Somalia, and Libya before landing in Darfur.

Weapons by Air, Fighters in Clinics

The reliance on air routes has intensified since 2024, when an RSF aircraft was shot down over Nyala, but flight permits continued to be issued. Seasonal flooding has rendered many ground routes impassable, making South Sudan a pivotal transit corridor in what observers describe as a UAE-backed supply chain.

The RSF’s footprint extends beyond logistics. Fighters wounded in combat are reportedly treated quietly in private clinics in Juba, while RSF-aligned forces maintain a presence in Western Kordofan and the Abyei border region.

Kiir’s UAE Connection

At the political level, Kiir’s ties with the UAE have deepened. His deputy for economy and finance, Benjamin Bol Mel, has emerged as Abu Dhabi’s chief interlocutor, negotiating oil and agriculture deals. Confronted by a deepening financial crisis, Juba has also sought loans from the UAE, giving Abu Dhabi growing leverage in South Sudan’s economy.

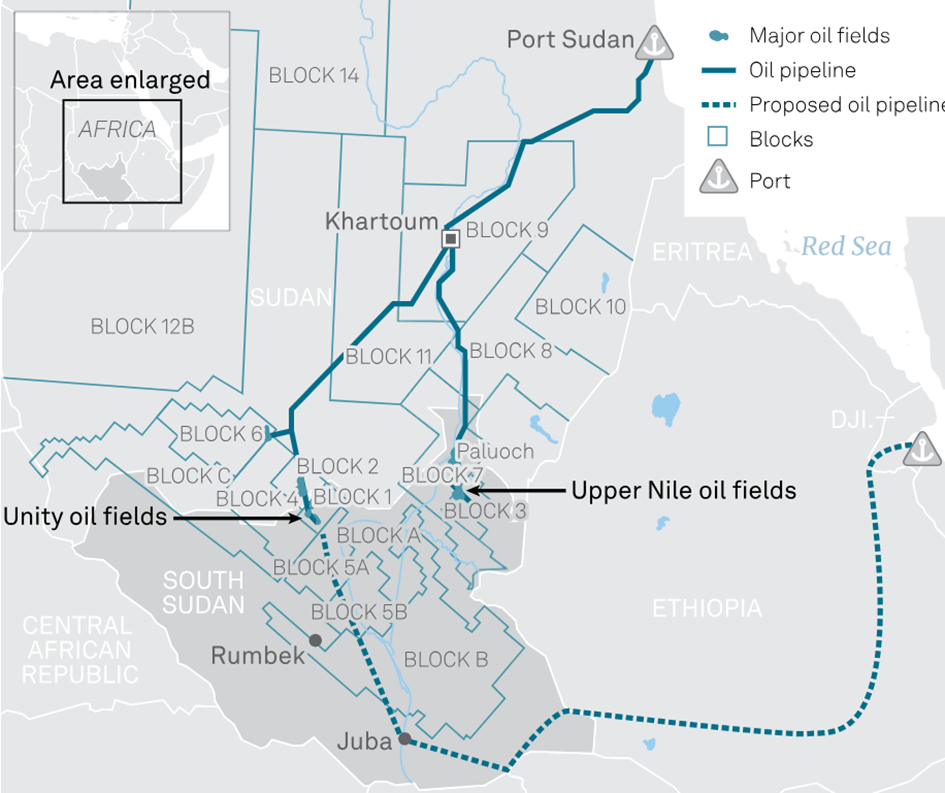

Analysts warn this threatens to dilute the long-standing dominance of Chinese energy firms, which control much of South Sudan’s oil sector.

Juba’s quiet cooperation with the RSF sits uneasily alongside its dependence on Sudan’s regular army (SAF), which controls the pipeline to Port Sudan—the landlocked nation’s only crude export route and its primary source of state revenue.

Ties with Khartoum have already frayed, particularly after Kiir dismissed his powerful security adviser Tutkew Gatluak Manime in January 2025. Gatluak had served as a key intermediary with Sudan’s generals.

Payback Against Machar

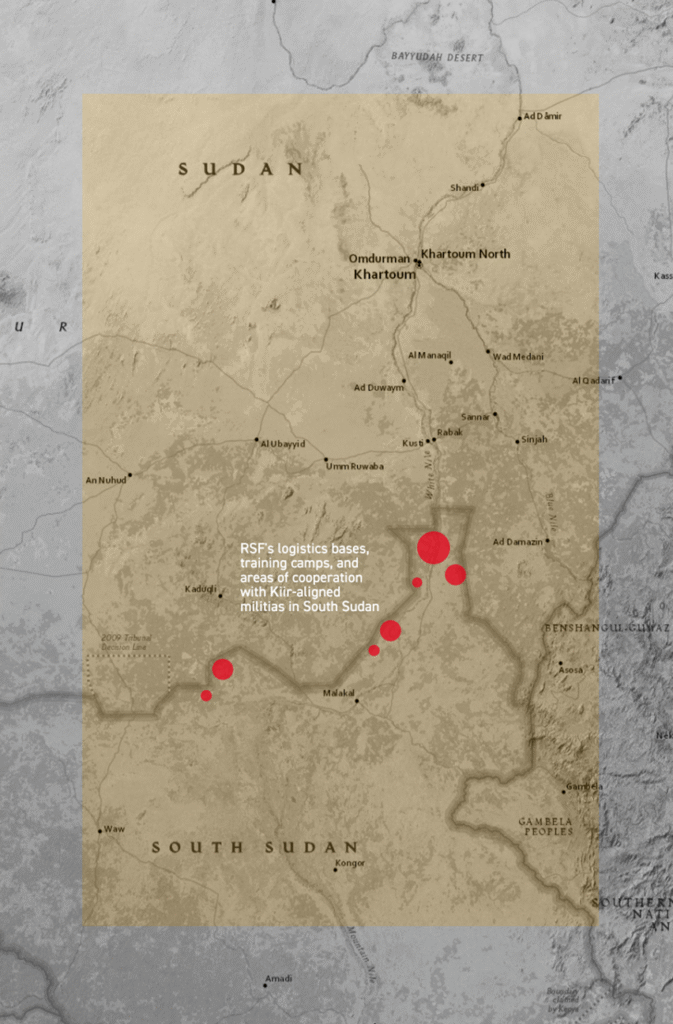

Local sources and field reports identify Dukduk, about 50 kilometers southwest of Renk town, as a major node. In March 2025, RSF fighters ambushed and overran an SPLA-IO convoy there, underscoring their ability to project force inside South Sudan. Another staging area lies near Bout, on the Sudanese side of the Blue Nile State border, where convoys are organized before crossing.

Joint training camps have also been reported in enclaves along the frontier, where RSF operatives work with militias aligned to President Salva Kiir, blurring the line between Sudan’s war and South Sudan’s fragile peace.

The RSF’s access relies heavily on cooperation with a Kiir-aligned militia in Upper Nile. This partnership provides safe passage through border crossings and protection for convoys moving arms, fuel, and fighters. In return, local militias benefit from RSF training, weapons stockpiles, and battlefield support.

The RSF’s role in South Sudan is not limited to logistics. Sources in Juba say the group has offered quiet backing to Kiir in his power struggle with rival Riek Machar, whose allies have recently been arrested and governors replaced. The moves have rattled the 2018 peace deal, which ended years of civil war by reintegrating Machar into government.

By targeting Machar’s base of support, the RSF appears to be repaying Juba for access and cooperation. But the strategy risks pushing South Sudan back to the brink of renewed conflict, with the fragile peace process under mounting strain.

South Sudan’s dual role—as a state reliant on Khartoum for oil exports and as a quiet facilitator of RSF logistics—underscores the shifting geopolitical dynamics in the Horn of Africa. As Sudan’s civil war grinds on, Kiir’s balancing act between the RSF, the SAF, and foreign backers such as the UAE and China may prove increasingly untenable.

The RSF logistics enclave is situated along the Sudan–South Sudan border in Upper Nile State, primarily in Renk County:

- Dukduk Area: Approximately 50 km southwest of Renk town, near the Bout–Dukduk road. RSF fighters ambushed and routed an SPLA-IO convoy here in March 2025.

- Bout Vicinity: Around 20 km west of Bout, Blue Nile State’s Tadamon locality, where RSF-aligned forces organize supply convoys and arms transfers.

- Joint Training Camps: RSF and a South Sudanese militia aligned with President Salva Kiir opened training and staging camps in border enclaves of southeastern Sudan, immediately adjacent to Upper Nile.

UAE could anger China in South Sudan

The United Arab Emirates’ entry into South Sudan in 2024 through a €12 billion oil-for-loan deal is reshaping the country’s economic landscape and raising concerns for China, long the dominant investor in Juba’s oil and infrastructure sectors.

Beijing’s state-owned giants CNPC and Sinopec have underpinned South Sudan’s oil production since independence in 2011, pairing energy stakes with infrastructure, health, and education projects. This broad-based approach reflects China’s strategy of securing resources while embedding itself in national development.

By contrast, Abu Dhabi’s loan—collateralized by crude exports until 2043 and worth nearly double South Sudan’s GDP—ties the country’s future oil output directly to Emirati interests. Combined with arms deliveries, gold exploration, and control over currency printing, the UAE’s highly concentrated leverage risks crowding out Chinese influence and altering the balance of power in Juba.

Analysts warn that as South Sudan grows more financially dependent on the UAE, Beijing’s long-term development-driven model may be undercut by Abu Dhabi’s debt-based, transactional strategy, setting up potential friction between the two powers in the Horn of Africa.